X.Blockchain Technical White Paper

Yongseok Kwon

May 21, 2018

Copyright © 2018 XBLOCK SYSTEMS CO., LTD. Without permission, anyone may use, reproduce or distribute any material in this white paper for non-commercial and educational use (i.e., other than for a fee or for commercial purposes) provided that the original source and the applicable copyright notice are cited.

DISCLAIMER: This X.Blockchain Technical White Paper is for information purposes only. XBLOCK SYSTEMS does not guarantee the accuracy of or the conclusions reached in this white paper, and this white paper is provided “as is”. XBLOCK SYSTEMS does not make and expressly disclaims all representations and warranties, express, implied, statutory or otherwise, whatsoever, including, but not limited to: (i) warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, suitability, usage, title or noninfringement; (ii) that the contents of this white paper are free from error; and (iii) that such contents will not infringe third-party rights. XBLOCK SYSTEMS and its affiliates shall have no liability for damages of any kind arising out of the use, reference to, or reliance on this white paper or any of the content contained herein, even if advised of the possibility of such damages. In no event will XBLOCK SYSTEMS or its affiliates be liable to any person or entity for any damages, losses, liabilities, costs or expenses of any kind, whether direct or indirect, consequential, compensatory, incidental, actual, exemplary, punitive or special for the use of, reference to, or reliance on this white paper or any of the content contained herein, including, without limitation, any loss of business, revenues, profits, data, use, goodwill or other intangible losses.

Abstract:The appearance of bitcoin and a sharp increase of bitcoin trading have proven that the blockchain technology is safe enough to be trusted as a transaction ledger. The main reasons why blockchain technology gets attention are: 1) Unlike the existing method, the Trusted Third Party (TTP) has been removed in terms of securing reliability; 2)since the information about all transactions is distributed to all participants in the network, it is virtually impossible to manipulate the transaction contents.

The most important key concepts in the blockchain technology are ‘Decentralization’ and ‘Distributed ledger’ concepts. According to conventional method, all transactions are recorded in a centralized central server, and the trust of the transaction was ‘guaranteed’ by this central server (trusted third party).However, transactions occurring on the blockchain are transmitted to all participants participating in the network and are ‘verified’, ‘agreed’, ‘bundled in blocks’ and connected in a sequential (linear) manner.

The size of the blockchain in which all transaction information is recorded becomes larger as the number of cumulative transactions increases, in other words, gets larger as time goes by. This means that someday it will become actually impossible for all participants of the network to store and manage the entire blockchain. In other words, a system (node) with enough performance to be able to store and manage the entire blockchain is gradually reduced in number and there is a high possibility that a relatively small number of node groups will be formed. And it will result in another form of centralization. If a relatively small number of node groups manage the entire blockchain, the reliability of the transactions will depend on this small number of node groups. In other words, it means that ‘decentralization’, the fundamental concept of the blockchain, can be seriously damaged.

In the application of blockchain technology, by proposing X.Blockchain transforming the blockchain connection structure from the existing linear structure to the multidimensional structure, we want to find a solution to the whole blockchain size problem and hence the problem of node concentration through this document.

Table of Contrents

- Problems

- Background

- X.Blockchain Overview

- Consensus Algorithm

- Asset Model

- Accounts & States

- Currency & Issurance

- Use Cases

Problems

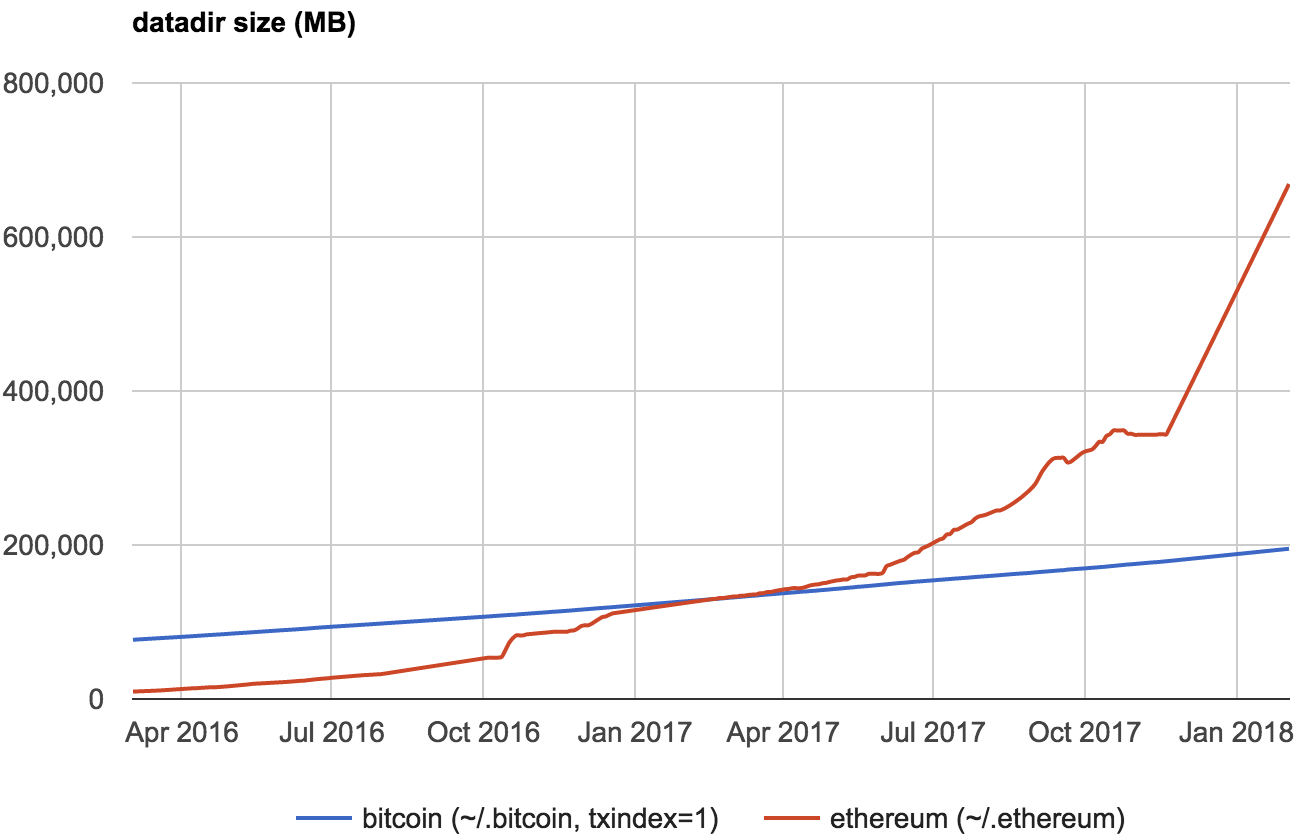

The size of the blockchain is bound to increase constantly in proportion to the cumulative number of transactions as time passes. The ledger is distributed and managed on all nodes participating in the blockchain network. In this way, when trying to stick to the basic concept of blockchain, that is, securing the trust of the transaction without the third trust party, the ever increasing blockchain size problem causes the limit situation in the participation of nodes for transaction verification. In other words, to participate as a full node 1 that stores and administrate the huge blockchain, a certain level of performance such as securing storage space is required. Since the performance level is continuously increased in proportion to the size of the blockchain, the numerical reduction of the participating nodes becomes inevitable, resulting in a further centralization2. As of May 2018, the size3 of the whole blockchain containing the transaction data of Bitcoin has already exceeded 200G and the blockchain data of Ethereum has recently surpassed 600G.

Bitcoin & Ethereum blockchain size - source: http://bc.daniel.net.nz/

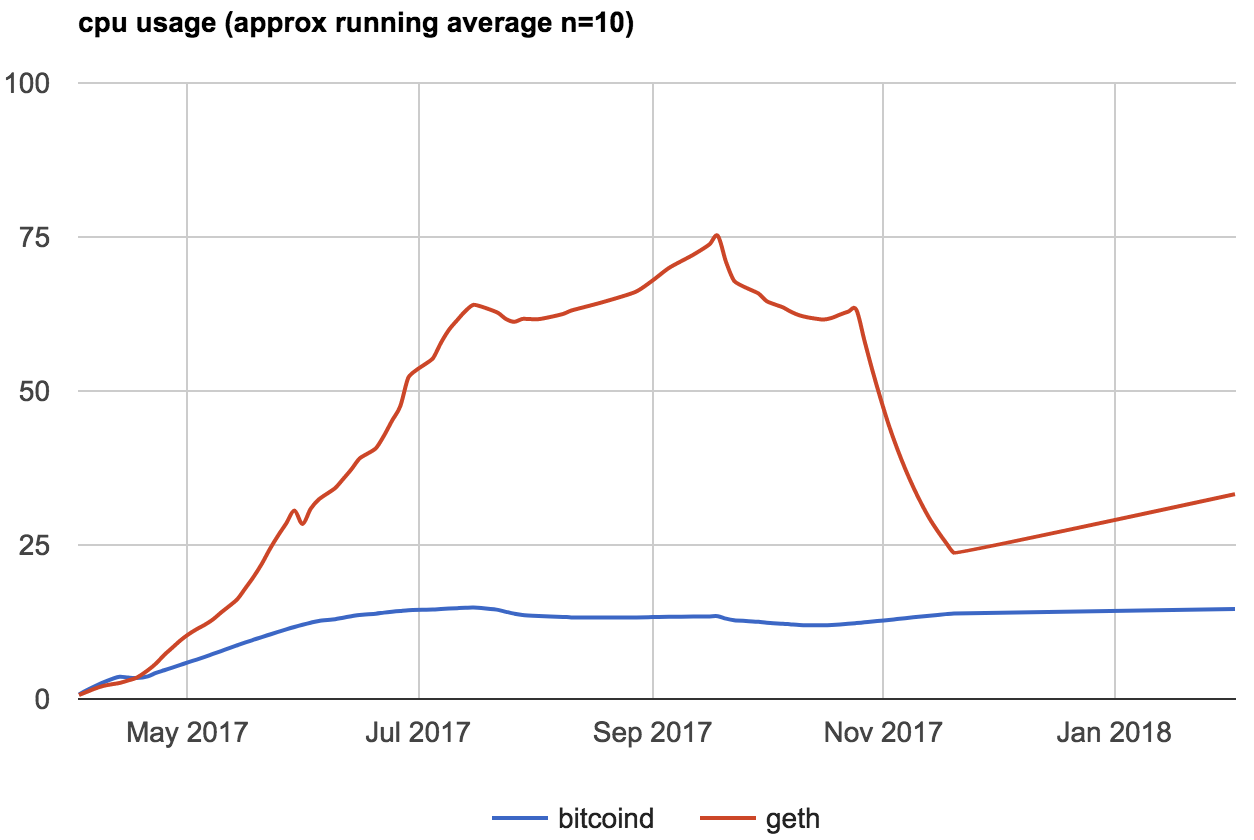

Bitcoin & Ethereum CPU usage - source: http://bc.daniel.net.nz/

This level of ‘eligibility condition’ makes it virtually impossible for an absolute majority of user clients (including the mobile devices) to participate in a blockchain network as a full node. As a result, the user client has to ‘commit’ to a relatively small number of full node groups without being able to judge the credibility of transactions on their own (without the trusted third-party institutions) and he has to unilaterally ‘accept’ the results. At this time a small group of full nodes acts like a ‘‘trusted third-party institutions’. This problem of the ‘centralization of full nodes’ is caused by the high computing power required for storing the large whole blockchain and the creation of blocks (mining) as mentioned above. Here, the reason why the storage of the whole blockchain is requested again is that because the structure of the blockchain is made up of the linear linkage structure, it is impossible to separate only necessary blocks. The set of intermediate disconnected blocks is of no value because it cannot confirm any credibility. The feature of such a blockchain is that it takes various inefficiencies despite its excellent innovation. For example, let’s say, a company decides to use a ‘public blockchain’ to make and manage internal department activity records. A blockchain node operated by the company must store a large number of transactions that are occurring on this public blockchain globally, independent of their own records. And this full blockchain data would probably (most likely) be hundreds of or thousands of times larger than the company’s transactions. From the perspective of the company, it is necessary to store and manage large amounts of data that are unnecessary, but not comparable to the data generated by them. To solve these problems, we can examine the use of ‘private blockchains’. Of course, the private blockchain is also important and it has a sufficient value, but it is not the solution for what we want in terms of having a centralized structure that is more than the problems raised above.

We constructed a set of transactions with meaningful relationships to all transactions submitted (generated) on a single blockchain network, while maintaining the same level of distributed architecture as the public blockchain. As a result, we propose a connection structure of independent and separate blockchains consisting of the transactions contained in each set. In this paper, we propose a structure and a method for selective blockchain configuration and management, which is beyond the constraint that all nodes participating in a single public blockchain network must manage the whole block.

X.Blockchain does not necessarily force all the generated transactions to be in one linear structure. This implicitly allows dispersion (fork) according to the transaction, which means that it is possible to construct an individual blockchain composed of transactions having a meaningful relationship. For example, when ‘document’ is used as a reference, ‘initial creation’ of each document is recorded in a blockchain (MainChain) having the same linear structure as the existing blockchain. However, additional transactions such as changes made to a specific document already recorded in the MainChain are recorded on SubChain, which is another blockchain that makes the corresponding block on the MainChain, not the MainChain, a genesis block. Again, in the example presented earlier, one company that intends to manage internal activity records on a public blockchain creates a block to be used as a Gennesis block in its blockchain in an existing MainChain. A separate SubChain is constructed starting from the block, and the company internal activity record is stored and managed therein. This allows the company to minimize the storage of transactions and blocks with different purposes.

Background

In a conventional blockchain, dispersion(fork) corrupts the consistency of the data written to the block. The presence of a plurality of blocks having the same block height by dispersion means that a single object at a certain time has a plurality of different status values at the same time, which is a contradiction by itself. That is to say, ‘A account balance is currently 2 million won and at the same time 3 million won’. Suppose you withdraw 2.5 million won from your A account. What is the balance of the A account after withdrawal? Is it possible to withdraw before that?

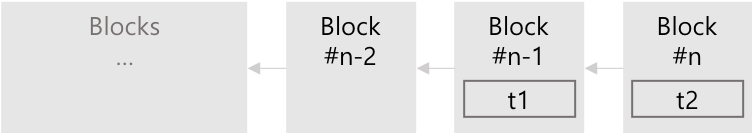

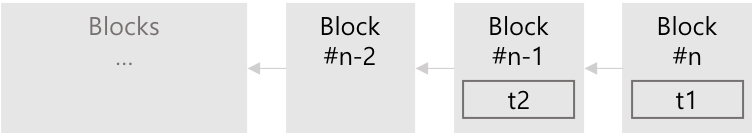

To avoid this problem, events that change the state of the same object must be processed sequentially. It means that the processing result for another event should be additionally reflected in the changed state after the processing for any event for changing the state is completed and the state change is confirmed. For example, the state of A is SA, e set of events that change it is called TAthe set of events that change it is calle t () is SA,t . Assuming a plurality of events t1 and t2, the processing of event t1 should be completed and the processing of event t2 should proceed after the state of A is determined as SA,t1 .The same is true in the case where t2 occurs in advance. As a result of the processing of t2, the processing of t1 should proceed in a state where the state of A is determined as SA,t2.

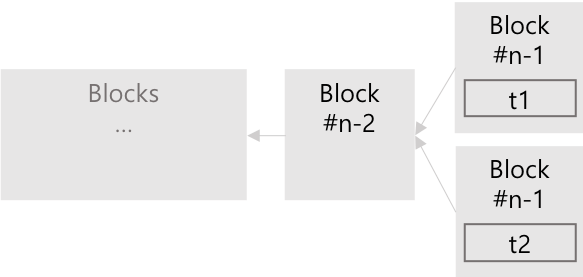

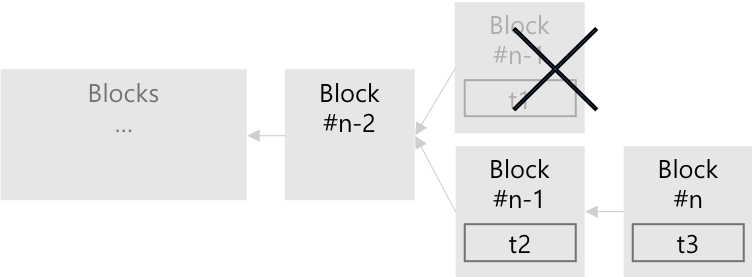

This is expressed as a block structure as follows.

or

However, if the processing for t2 is performed simultaneously before the processing of t1 is completed for SA, and if the previous state of A at the time of event t1 is processing is defined as SA,t0 , the previous state of A at the time of event t2 is processing is also SA,t0 ,so SA,t0is dispersed to two type state, SA,t1 and SA,t2 .

This is the case when a typical double payment problem occurs. To solve this problem, at some point (block height = # n-1) the SAmust be forced to only one. That is, the final state of the SAmust be determined as either SA,t1or SA,t2 , which means that any one of event t1 and t2 must be canceled (invalidated).

This explains that not all events that cause a state change of the same object can have concurrency, and that sequential processing must be enforced. In the case of a crypto currency transaction, the event (transaction) does not change the status (balance) of any one account, but changes the status of multiple accounts, including remittance and receiving accounts. At the same time one account can trade potentially with all accounts except for itself. When there are transaction t1: A → B and transaction t2: A → C, t1 changes the state(balance) of A and B simultaneously. Thus, it belongs to the same set of events as other events that change the state of A and B. And t2 also changes the state of A and C at the same time, so it belongs to the same set of events as all other events that change A and C. As a result, events that change states of A, B, and C, including t1 and t2, all belong to the same set of events. If we assume t3: D → E, t3 can be classified as a separate the set of events because it is not related to the state changes of A and B. However, since D or E will also be able to trade with A, B, and C, consideration should be given to the posibility that the state of D will be synchronized with the state change of A due to these potentially occurrences (and so is E). If the state change of D belongs to the set of events Ti and then belongs to another the set of events Tjdue to another account and new transaction, Ti and Tj should eventually be included as a subset of the larger the set of events that must be guaranteed sequentiality. As a result, it is convenient for all events for A, B, C, D, and E to consist of a single the set of events. In the end, the state that should be managed here is not the state of each individual account but the state of a single ‘transaction history ledger’ in which transactions among unspecified number of accounts are recorded.

X.Blockchain Overview

- MainChain: This is a upper blockchain composed of a linear block linkage structure and it is possible to have multiple SubChains. The MainChain can be a SubChain of another upper MainChain.

- SubChain: An independent blockchain consisting of specific blocks of MainChain as genesis blocks. A SubChain can be a MainChain of another lower subChain.

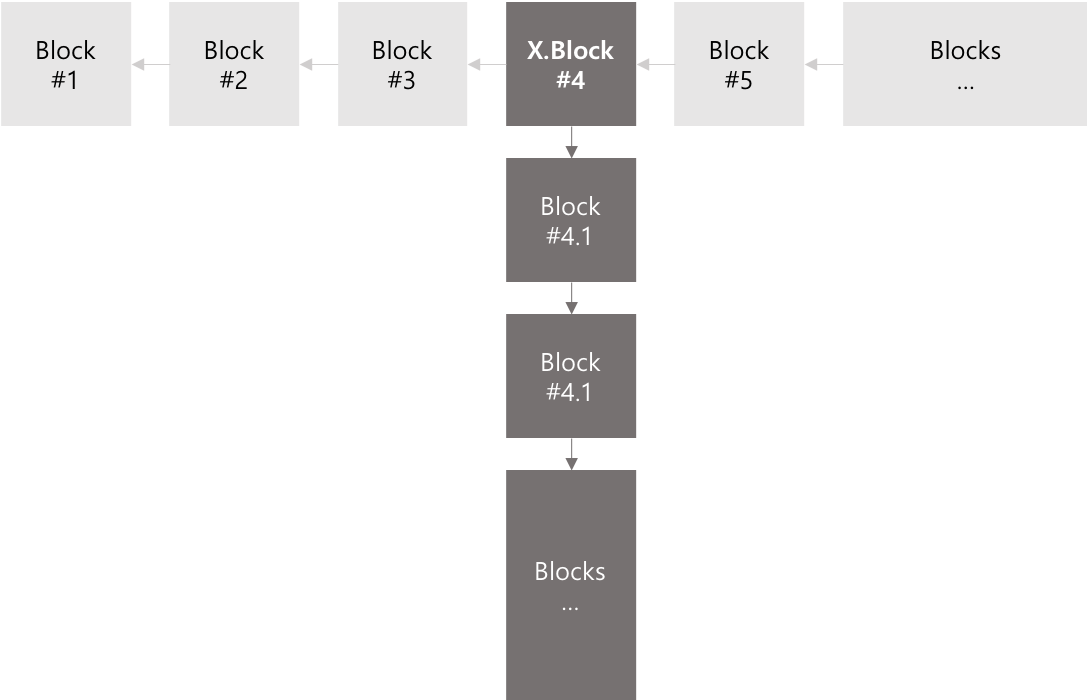

- X.Block: A block that acts as a Genesis Block of the SubChain among the blocks constituting the blockchain.

- X.Transaction: Transaction to create X.Block.

- Full Node: Node managing MainChain and all lower SubChain blocks.

- Sub Node: A node that manages only a block of a specific SubChain.

- Blockchain Depth: The Depth of the SubChain to be managed based on the top level blockchain managed by the node.

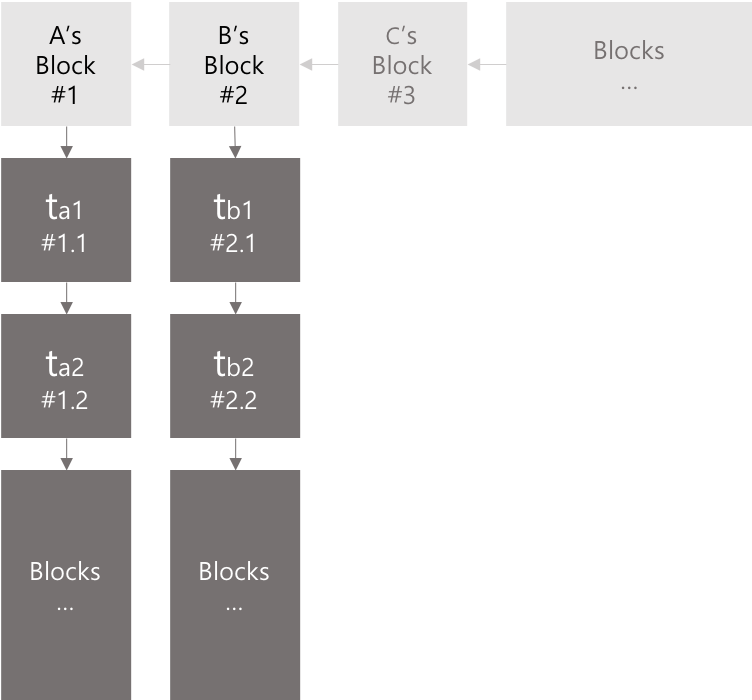

Previously, we have focused on the double payment problem the reason why the existing blockchain must be limited to a linear structure. All events that cause state changes on the same object can not have concurrency, and sequential processing must be enforced. However, in the case of events that change the state of the different objects, they are not ‘necessarily’ processed sequentially. For example, if the event is about documents that exists independently of each other, the state change of a certain document does not have a meaningful relationship with the state change of another document4. Since the individual events (each document change) apply only to one object (here a specific document), the events need not be synchronized with respect to each other. In other words, even if the status of multiple documents changes at the same time, no contradiction such as the double payment problem mentioned above will occur. Sequential processing of events is meaningful only between events that cause the state transformation of the same object.

This means that if multiple different objects (documents) is called and A, B, C … Each set of events is called TA, TB, TC, … , each the set of events can be composed of one independent linear structure. That is, the events ta1 and tb1 belonging to different the set of eventss TA and TB do not have to be sequentially processed with respect to each other or included in the same serialization structure.

X.Blockchain constructs the set of events T as an independent blockchain. Through this, it is desired to develop a blockchain of a single linear structure into a blockchain of a multidimensional structure composed of set of a plurality of individual blockchains. Each blockchain, which is constructed individually and independently, does not contain unnecessary blocks due to a set of events that do not have a meaningful relationship. Events recorded in the same blockchain consist only of events that have a meaningful association with each other by some criterion. The blockchain can be selectively maintained and updated on the basis of the relationships contained in each of the blockchains thus structured, and the trust based on the blockchain can be constructed more efficiently.

MainChain

It has the same structure as a general blockchain of a linear structure. MainChain records in sequence various records including transaction details of asset and makes the connections and expansion of blocks in the same structure as other blockchains. However, a special block that can be dispersed among the blocks of the Mainchain can be created, and the linkage and expansion of another block can be started from this block.

SubChain

SubChain is another block linkage and extension that starts on a special block that is present on the MainChain and can be dispersed. Multiple blockchains starting from a special block in MainChain consist of independent blockchains that are not synchronized, by means of generating each block consisting of transactions belonging to an independent set of events and being linked the resulting block to the last block in each blockchain. In this case, the independent blockchain for each set of events in the disjoint relation with the other set of events is called SubChain. A SubChain is itself a complete and independent blockchain. The mechanism to reach all the functions and consensus on the SubChain is exactly the same as that of MainChain. Since it is possible to create an X.Block on a SubChain as just like on MainChain, SubChain can be a MainChain of another SubChain. This allows X.Blockchain to evolve into a multidimensional blockchain structure.

X.Block

Since sequentiality between events belonging to the same the set of events like a trade of crypto currency must be guaranteed, blockchain should be expressed in a single linear structure. So XBlock, which is allowed to be branched, cannot deal with transactions such as asset transfer. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between X.Block that allow for dispersion while not including transactions such as asset movement, and general block that do not allow dispersion, including transactions such as asset movements.

A special block that can branch is called X.Block. Only one SubChain can be started from a particular X.Block. However, the SubChain can contain another X.Block and in result X.Blockchain can evolve into a multidimensional blockchain structure.

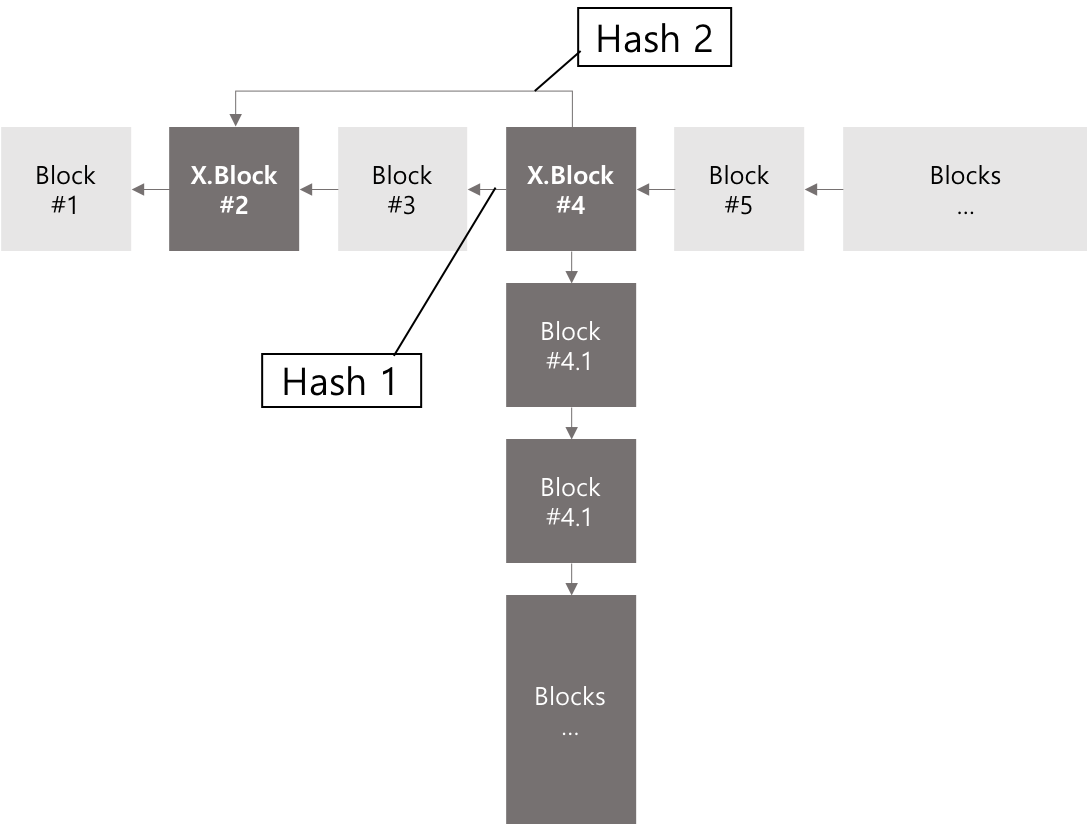

All blockchains on X.Blockchain (MainChain & SubChain) are consisted of combination of two types of blocks, X.Block and normal blocks. In addition, X.Block has a plurality of hash linkage structures unlike a normal block. It is that an X.Block has a hash connection with the previous block (normal block) and concurrently with the previous X.Block. The reason for having such a multiple linkage structure is related to X.Blockchain’s departure to ensure the more efficient integrity of all ‘electronic data’ including electronic documents. If only the integrity of ‘data’ is to be verified, data validation is possible by maintaining only the SubChain containing the data and the upper MainChain of the SubChain, which is an important motive for the X.Blockchain proposal. However, when frequent asset transactions occur on MainChain, the number of generic blocks that record them must be included in the maintenance object, so that the original efficiency of X.Blockchain is severely damaged.

X.Block has a ‘multiple hash link structure’ to solve the efficiency of ‘data’ integrity verification and the verification of the integrity of the asset transaction (transaction ledger). If the client is only for the purpose of verifying the integrity of the data on X.Blockchain, it is possible to construct a blockchain which is necessary for verification of all ‘data’ contained in the SubChain, only by maintaining a part of MainChain consisting only of X.Blocks and a specific SubChain, without maintaining normal blocks. At this time, ‘a part of MainChain consisting only of X.Block’ must have a single block connection by itself. Therefore, X.Block has an additional linkage structure with the previous X.Block in addition to the connection with the normal block.

X.Transaction

A special transaction for creating X.Block is called X.Transactioin. X.TX should describe the characteristics of the generated SubChain, the properties and initial state of the asset to be created on this SubChain. This is similar to the sum of the content of the genesis block in a generic blockchain and the description of the ‘token’ generated by smart contract in etherium. X.TX should describe the following.

- Target ChainID

- SubChain's Name

- SubChain Asset's Name & Code

- Initial State of SubChain Assets

- Initial Validator Set

- Tx. Fee in MainChain Asset

The processing fee of X.Transaction is paid as the asset of MainChain. The processing fee for Tx. processing should be different from the general Tx. processing fee, but the decision of this will be delegated at the discretion of the person who creates and verifies blocks. To increase the efficiency of the whole blockchain by preventing the excessive occurrence of X.Transaction leading to unnecessary X.Block and SubChain generation, it is correct that a commission is charged higher than the commission of the general Tx.

Consensus Algorithm

X.Blockchain basically reaches consensus by using the PBFT + DPoS mechanism. This is a consensus mechanism proposed by Tendermint, which makes it possible to construct a public & private blockchain by combining the DPoS concept with the conventional PBFT algorithm.

PBFT (Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance)

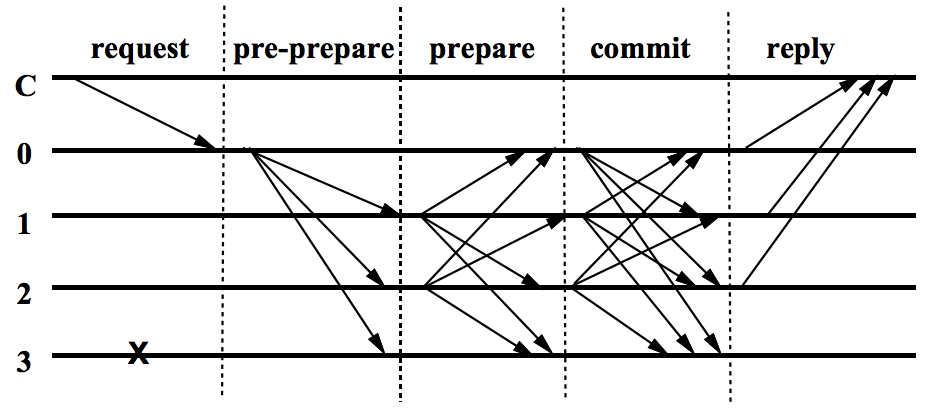

PBFT is a consensus algorithm introduced in the late 90s. The existing BFT was able to operate with the assumption of a synchronous environment and had too many performance problems for practical use. It is PBFT what improves such BFT to be able to operate in asynchronous environment, and solves high-speed transaction processing while solving the Byzantine generals problem.

In the PBFT-based consensus algorithm, if or more of all nodes (n) participating in the consensus agree to accept the proposed block, by confirming the proposed block and linking it to the next block in the blockchain , it guarantees that the consensus will be reached in any case to the extent that the proportion of malicious nodes does not exceed

.

PBFT algorithm - source: http://pmg.csail.mit.edu/papers/osdi99.pdf

In the PBFT-based consensus algorithm, there exists a primary node that proposes a first block. This Primary node acts to propagate the generated transactions to other nodes (replicas) on the network by sorting them in the order of requests. The following is a brief description of all the consensus process of PBFT.

- The primary node collects all transaction requests from the client.

- The primary node arranges transactions in the order of requests and constructs them into blocks and propagates them to the blockchain network.

- The Replica node propagates the block received from the primary node back to the other Replica nodes.

- Each Replica node confirms whether the block it propagated is the same as the block received from another node. If the number of nodes transmitting the same block exceeds the quorum

, it verifies the block.

- And then it propagates the validation result of the block to other nodes.

- Each node aggregates the block verification results which were sent by other nodes. If the same result exceeds the quorum

, it connects the block to its own blockchain. Otherwise, it does not connect the block to the blockchain.

- Sends the result to the client.

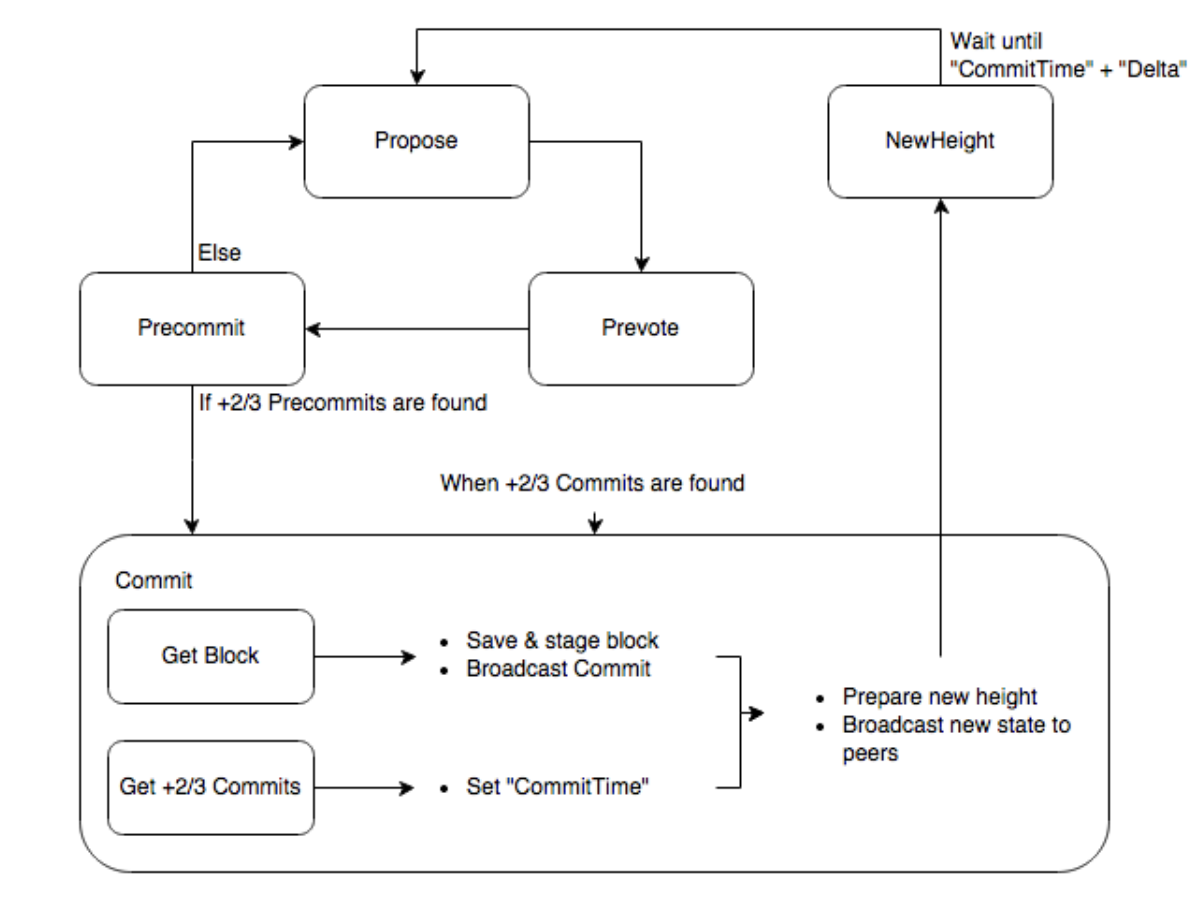

PBFT-based algorithms that are heavily used currently are based on the basic consensus procedure as described above. One of them is PBFT + DPoS which is adopted by Tendermint. In the Tendermint consensus procedure, the primary node is referred to as a Proposer, the Replica node is referred to as a Validator, and not all the nodes on the network become Validators, only the node that holds their own stakes becomes a Validator and participates in the settlement process. In the conventional PBFT, all nodes have the same weight, but in the Tendermint’s consensus algorithm, each Validator has a weight proportional to the amount of the stake, so the quorum is not the number of Validators but of the whole amount of the voting power of the Validators.

Tendermint Consensus Procedure - Source: https://tendermint.com/static/docs/tendermint.pdf

For more information on the PBFT + DPoS consensus mechanism, see the Tendermint document.

Validators and Delegators

Validator is a node participating in the verification and consensus process of the block. The nodes included in the Validator set decide whether to agree to the proposed block by voting based on their voting power. All the nodes constituting the network can be Validators by reserving their own stakes, but it is not always possible because the maximum number of nodes constituting the Validator set is fixed. If the number of nodes making up the current Validator set is the maximum, then the only way to make the new node a Validator is to deposit a larger stake than the Validator that holds the smallest of the current Validators. In this case, the Validator with the smallest stake will be deactivated, and the new node that holds the larger stake will serve as the Validator. Even if it is not a Validator, there is a way to participate indirectly in the consensus process. It is to delegate stake to a specific Validator. Every node on the network can delegate stake to a specific Validator. This node is called Delegator. The voting power of the delegated Validator will be increased by the delegated stake, and the compensation to be received by the Validator will also increase accordingly. At this time, the Delegator that has delegated his own stake will also receive a portion of the compensation that the Validator will receive as compensation for delegation. The stakes that have been deposited to become a Validator are bound to be unavailable while the node is acting as a Validator. If the Validator performs malicious actions such as not following the agreed consensus mechanism, some of or all of the deposits will disappear. This is a kind of punishment concept for the unfair conduct of the consensus process, which solves the Nothing at Stake problem of the traditional PoS algorithm.

Proof of Forkability

Because of the special block-linking structure of X.Blockchain, it is not possible to apply already known consensus mechanism as it is. No consensus mechanism exists because there is no consideration for ‘the acceptance of dispersion’ proposed by X.Blockchain. In other words, X.Blockchain requires an additional consensus process considering the acceptance of dispersion. That is, ‘Generation of X.Block’ and ‘Link of a new block to a specific SubChain’ are legitimate. The proof method considering the acceptance of dispersion is called as Proof of Forkability (PoF), and this is a key component of the consensus mechanism used in X.Blockchain with PBFT + DPoS.

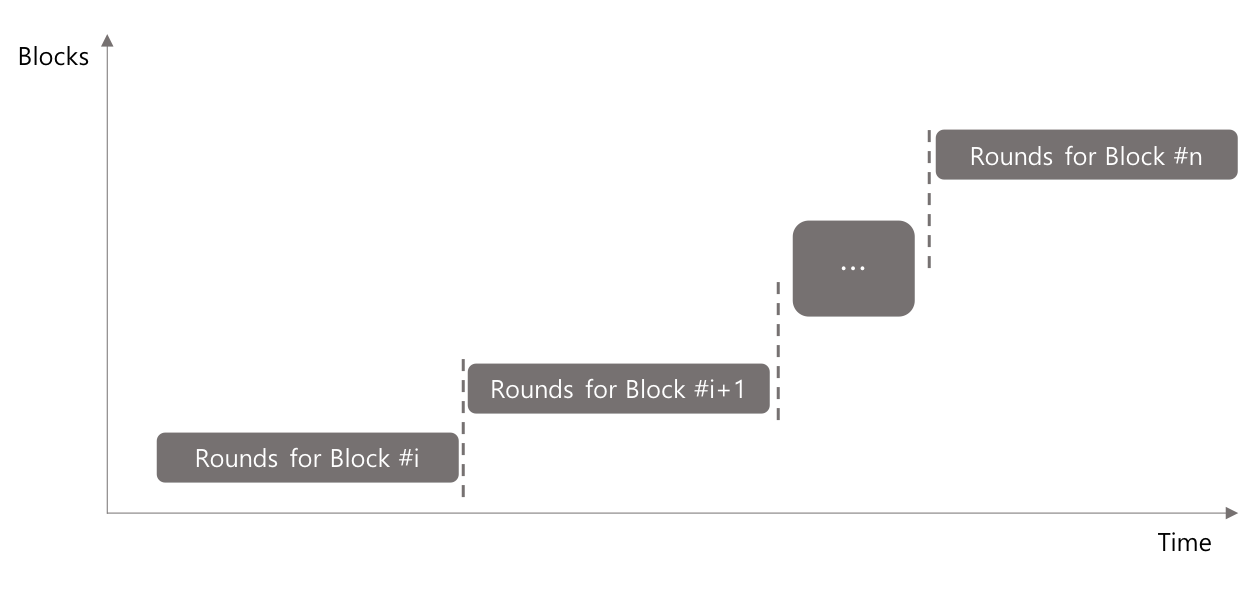

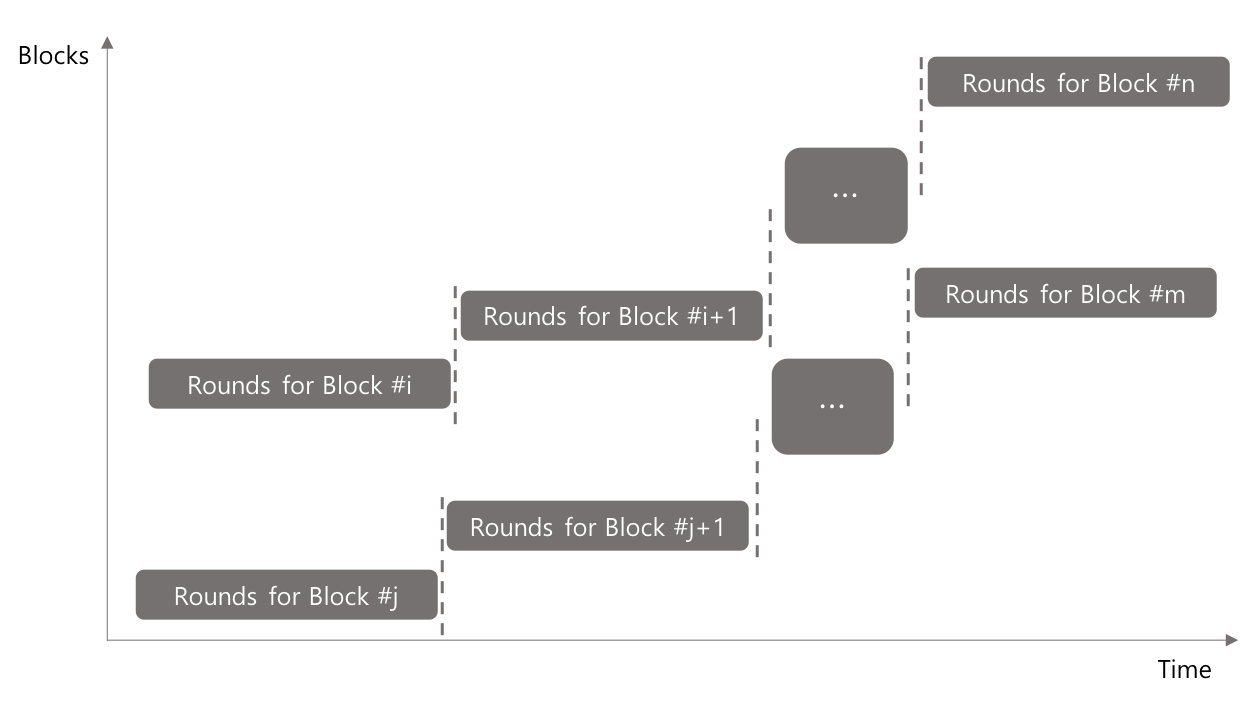

In the BFT-based consensus mechanism, the consensus process for the proposed block consists of many number of rounds, and each round consists of a plurality of stages. The processing for the next block(the processing of the transaction to be included in the next block) must be delayed until the consensus process for the specific block is completed and the corresponding block is connected to the blockchain. However, in the PoF, a consensus procedure for a plurality of blocks can be performed in parallel. Blocks belonging to different SubChains may be ‘proposed’ simultaneously and the procedure of consensus for each block does not need to be synchronized with the outcome of the consensus procedure for other blocks.

Of course, within a single SubChain, synchronization must still occur between consensus procedures for creating a block, but in the context of an whole blockchain, more blocks within the same time can be created without compromising security, which results in faster and more efficient transaction processing.

X.Tx confirmation

When X.Tx is submitted on the network, it checks the validity of each field value constituting the transaction and the electronic signature of the submitter who submitted the current X.Tx are confirmed, and confirm whether sufficient assets to pay for the account to create the X.Block exist . Once the validation for X.Tx is confirmed, an X.Block is created and submitted to the Validators. At this time, X.Block is given a unique block number, which is the ChainID value of the SubChain starting from the current X.Block.

X.Block confirmation

When X.Block is submitted, each Validator will go through the confirmation process for the included X.Tx again. And then the hash link between the block number assigned to X.Block and the previous blocks is checked. As mentioned above, since X.Block has a double hash link structure, both hash linkages must be confirmed. When this process is completed, the signature of the Validator for the current X.Block is made, and the signed X.Block is submitted to the other Validators again, and the procedure of the PBFT consensus algorithm proceeds.

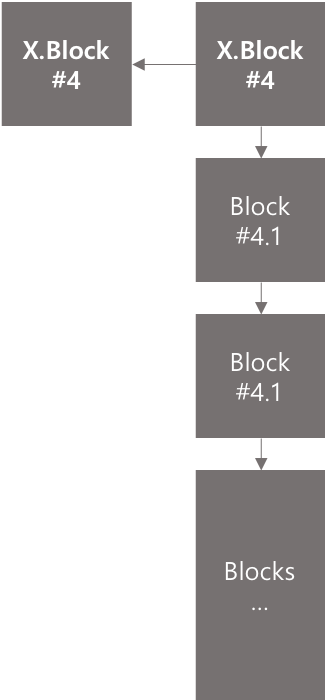

Forking from X.Block

Up to two blocks can be connected to X.Block. The first block is the main block followed by X.Block. This block has a block number the block number of X.Block + 1 . The second is the block that is connected after X.Block on the SubChain that is created starting from X.Block. The block number of this block is of the form {ChainID}.{N} . Here {ChainID}is the block number of X.Block in MainChain, and {N}is the block concatenation order in the subchain. If the block number is 100, the block number of the tenth block is 100.10in the subchain of X.Block. Similarly, the block number of the 20th block in another SubChain starting from the 200th X.Block (block number:100.200) existing in the SubChain is 100.200.20 .

Asset Model

X.Blockchain can generate multiple SubChains and can continue the linkage through X.Block which can be dispersed. However, this dispersion in X.Block causes a ‘double payment problem’ in transactions of asset(cryptocurrency, coin). Therefore, there should be no correlation between the transaction ledger that is managed on the MainChain and the transaction ledger that is managed on the SubChain, and to solve this problem, we should thoroughly separate the account managed by each blockchain or should separate the asset itself (transaction ledger itself).

X.Blockchain separates assets. In X.Blockchain, the assets on MainChain, the assets on SubChain, and the assets on another SubChain are all different assets. In other words, all SubChains, including MainChain, have their own assets (coins) and an independent transaction ledger that records the status of these assets. The assets on each SubChain are principally forbidden by mutual transfer of assets between different trading mechanisms. However, according to the Communication between SubChains procedure to be added to this white paper in the future, it will be possible to move assets between different SubChains.

Accounts & States

The recording of all the impossible status data such as transaction between each account, data change for integrity check is recorded using IAVL + tree structure on the X.Blockchain. The various state values handled by X.Blockchain are stored in a key-value format. Each key-value pair forms an IAVL + tree structure, and the Merkle Root Hash that the highest hash value of this tree is determined. In other words, The state change of a specific account leads to the change of the Merkle Root Hash value and this Merkle Root Hash value is included in the block so that the state of the whole account is reflected in each block. This tree structure follows a variant of AVL Algorithm when reconstruction is required due to addition or modification of new nodes has a time complexity of O(log(n)). Since each SubChain has independent assets, the transaction ledger representing the status of each account’s assets must also be independent for each SubChain. Therefore, each SubChain has its own IAVL + tree structure for independent state management of accounts.

Currency & Issuance

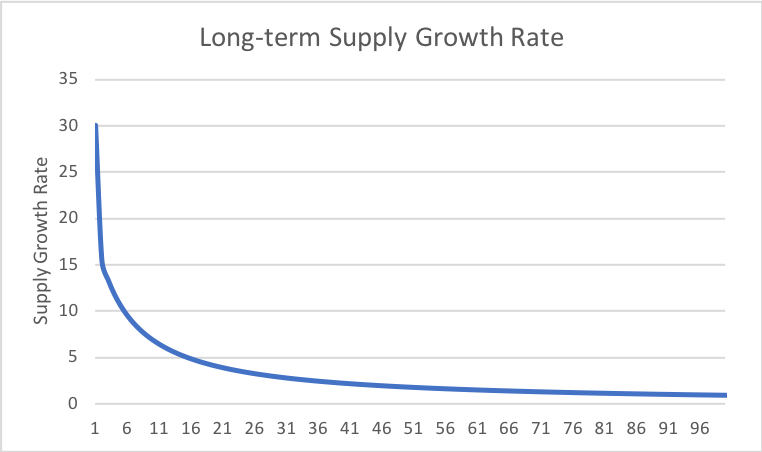

At present, X.Blockchain’s assets ATX has been issued with a total of 1,000,000,000 ATX, including the amount supplied through ICO and the retained earnings. The current total issue volume will be maintained until before X.Blockchain’s main net open, and thereafter the total issue volume will increase gradually depending on additional issues. Additional issuance of ATX will mitigate ATX centralization that may occur over time. If appropriate additional issuing methods are not provided, ATX may be concentrated in some block producers as compensation for block generation over time, and as a result the actual amount of money circulated on the market will decrease. Without further issuance and provision, the strong incentive needed to maintain a blockchain network will disappear, or at least will be reduced to a serious degree. In a public blockchain network, where higher levels of trust can be secured by the involvement of block producers, this can lead to fatal problems. On the other hand, unlimited additional issuance causes inflation, which reduces the real value of money, and this, as mentioned above, can cause problems such as weakening the motivation of the participants in the blockchain network. In this regard, if you look at the currency-related policies of the representative public blockchain ethereum, ethereum explains that that it is possible to mitigate the phenomenon of ‘wealth concentration’ by allowing a predetermined amount of ethereum to be issued and supplied annually. Since the additional supply is always the same, the proportion of the additional supply in the increasing total volume will continue to decrease. As a result, the long-term supply growth rate converged to zero and it also provides opportunities for current or future participants to continue to obtain ethereum through mining rather than market. At the same time, it is said that the amount of ethereum to be issued will balance with the amount of money that will disappear due to users’ carelessness over time. Below is a part of the Ethereum white paper.

The permanent linear supply growth model reduces the risk of what some see as excessive wealth concentration in Bitcoin, and gives individuals living in present and future eras a fair chance to acquire currency units, while at the same time retaining a strong incentive to obtain and hold ether because the “supply growth rate” as a percentage still tends to zero over time. We also theorize that because coins are always lost over time due to carelessness, death, etc, and coin loss can be modeled as a percentage of the total supply per year, that the total currency supply in circulation will in fact eventually stabilize at a value equal to the annual issuance divided by the loss rate (eg. at a loss rate of 1%, once the supply reaches 26X then 0.26X will be mined and 0.26X lost every year, creating an equilibrium).

Long-term Supply Growth Rate

X.Blockchain uses a model with fixed amount of additional issuance (permanent liner supply growth model) as the basic policy by reference to ethereum’s model. We will continuously revise this value through sufficient review and test of problem such as setting a supply growth rate relative to the initial issue volume of ATX and maintaining substantial money supply and inflation. And the optimal value of initial supply growth rate will be finally determined at the time of main net opening. Of course, consensus on the change of this value will be possible after the main net, but at the present time the mention of it will be a forecast with uncertainty, so we omit the description.

The long-term supply growth rate of X.Blockchain

Incentives

Additional issued assets will be paid as compensation for block creation. X.Blockchain is based on a PBFT-based consensus algorithm. Additional issued assets will be paid to these validators as compensation for block validation and expansion. In addition, X.Blockchain applies a DPoS consensus algorithm and provide the way to receive a portion of the additional issued assets, even if it is not a validator. All nodes on X.Blockchain can become delegator by ‘delegating’ their own equity to the desired validator. Nodes that could not become validators indirectly participate in the negotiation process as a delegator through this equity delegation method. It would be paid a portion of the reward the validator will receive. The question of the amount and the proportion of the additional issuing assets to be paid to validators and delegators will also be carefully determined through sufficient review and testing as a matter related to the issue of determining the supply growth rates mentioned above.

Use cases

Management system of the certificate of individual resident registration

Assuming a situation in which the certificate of individual resident registration is converted into the electronic document and managed by applying blockchain technology, this paper explains how the application of X.Blockchain differs from the application of existing blockchains, It is assumed that there is one certificate of individual registration for each person among the whole population and that it constitutes one block, and it is assumed that the certificate of individual resident registration is updated as much as the moving population every year and this is also recorded as one block.

| Classification | 2016 |

|---|---|

| Number of migrants | 7,378 |

| Ratio of migration (%) | 14.4% |

| Number of address transfers reported | 4,636 |

| Sex ratio of migrants (women=100) | 103.9 |

Source: National Statistical Office 「Domestic Population Transfer Statistics」, [Unit: 1,000 people,%, thousand cases]

According to the National Statistics Portal(http://kosis.kr), the total population in the Republic of Korea was 51,525,338 people as of the end of 2015. There must be a copy of the certificate of individual resident registration for each person among the whole population and the certificate must be renewed whenever the migration occurs, and according to the data in the table above, it can be estimated that there would have been total 7,378,000 cases5 of renewal to the certificate of individual resident registration during the whole year of 2016. If this is implemented by the linear blockchain, the initial blockchain will consist of blocks as many as the total population, and blocks should be added each year as many as the number of people who migrated. If it is applied from 2016, the number of blocks in the blockchain at the end of 2016 will be as follows.

And if we assume that 7,000,000 people migrate on average each year, 7 million blocks will be added annually. Here, if we assume that the size of each block is 80 bytes6, the size of the whole blockchain that accumulated the records for 10 years is calculated as follows

That is, in the case of blockchains of the linear structure, the size of blockchain accumulated for 10 years, 9.1G and the annual increment for future modifications of 0.52G will increase linearly.

If X.Blockchain is applied to the same scenario, though the number and size of total blocks are the same, the blocks added each year for modification will be organized into the SubChains, but not linked to the MainChain in a linear pattern. That is, the 70,000,000 blocks for the modifications for 10 years will be dispersed and organized into the SubChains underneath the MainChain consisting of 51,525,338 blocks. If the degree of dispersion of the modification blocks to the SubChains under the MainChain is evaluated based on simple arithmetic average, there will be 1 SubChain for each block of the MainChain and each SubChain will have 1.357 blocks. Based on this, the size of the blockchain per person among the whole population is as follows.

Apart from the blockchain of the linear structure, X.Blockchain makes it possible to selectively administrate the necessary data. If for some reason it is possible to have services such as individual resident registration for one million people, in this case, the total storage space necessary for verification of the modification history to the certificates of individual resident registration for 10 years for 1 million people can be calculated as follows.

In the future, the size of blockchain will be increased only as much as the size of the annual average modification blocks for 1 million people each year.

The scenario assumpted in this chapter did not take into account the increase in MainChain caused by new birth and the change (increase)8 in SubChain due to death, marriage, divorce, and other reasons. For this reason, in practice, a larger whole blockchain will be required. Also, the criteria of categorization of MainChain does not necessarily have to be one person among the whole population, nor does it have to contain a single transaction in one block. Therefore, the value calculated above does not have the real meaning, but has only meaning as a relative value for the comparison between the blockchain of the linear structure and X.Blockchain of the multidimensional structure. However, whereas the above example included only 1 type of document, the certificate of individual resident registration, the same scenario may be applicable to a diversity of public documents at the same time in reality. The more documents added, the greater the relative efficiency of the multidimensional blockchain versus the linear blockchain. Assuming that the above example adds one proof sheet from another public institution and that the transaction, such as document change history, occurs at a similar rate to the individual resident registration, in the case of linear blockchain, doubled number of blocks are additionally required. If another document is added, the same block is incremented as well. However, in the case of X.Blockchain, there is no change in the size of MainChain, and since the addition of blocks by the added document type is performed only on the SubChain, the relative efficiency of the X.Blockchain with the multidimensional structure becomes higher.

1. The full node means the node to mine the new blocks after storing the whole blockchain. ↩

2. As a solution to this problem, the Bitcoin side proposes SPV. This is a method to minimize the resources required by conducting the authentication of transactions only with the information at the block headers excluding the transaction data and is indispensable in the application of blockchains for electronic documents. If it is the transaction details that compose the transactions as it relates to the cryptocurrency, the electronic document data comprises the major part of transactions in the electronic document applications. At this time, the size of document is large enough to render the comparison with the transaction details of the cryptocurrency meaningless and therefore the blockchains do not contain the document data itself. Unless otherwise noted in this document specifically, the ‘size of blockchain’ refers to the ‘size of the blockchain header.’. ↩

3. Size of the whole blockchain including all of the transaction data describing the transactions and the block header information. ↩

4. If there is such a thing as a cross-reference between documents, a change of contents in the document may cause a change in the content of another document that references it, but the problem of cross-reference relationships between documents is only the individual state of each document but is not the object of transformation of same state as the condition to be included in the set of same events. ↩

5. According to the data published through the National Statistics Portal, the accurate number of persons who migrated in 2016 is 7,378,383. ↩

6. The size of Bitcoin block headers is 81 bytes. ↩

7. This corresponds to the average number of migration for 1 person of population for 10 years. ↩

8. As the increase portion to the sub-chains becomes larger, the efficiency of the X.Blockchain of the multidimensional structure will be the higher. ↩